Module 2: How to Design Your First- Year Writing Seminar

“How do I know what I think until I see what I say?”

--attributed variously to Graham Wallas (1926) and E. M. Forster (1927)

“I never understand anything until I have written about it.”

--Horace Walpole, 1717-1797

Having planned how to grade the major papers in our Core 110 seminar, you might be wondering how you will guide students toward completing the papers themselves. This module introduces some design principles for writing courses that can help you structure your seminar. Some of them may be familiar, and some of them may be so basic you think we are being condescending. Please use what helps and dismiss anything that does not!

But before we get to those principles, we ought to observe the unique demands of a seminar like Core 110. As a student’s introduction to liberal arts inquiry at Carroll, it puts before them ideas, knowledge, problems, and controversies that could be explored without writing a single word. This is the “seminar” part of the course, and it’s the part that can tempt us into “covering” material as we might do in any of our content courses. But as a writing seminar, we have a special obligation to help students meet the writing challenges they will face throughout their college education and beyond. A well-designed seminar, therefore, must integrate seminar content with writing instruction.

Writing instructors seek to integrate content with writing through the concepts of “writing to learn” and “learning to write.” Stated briefly, “writing to learn” makes writing the means of inquiry, not the event that happens after having inquired. The above quotations from Wallas, Forster, and Walpole make the point that understanding is a product of writing, whereas the conventional view has it the other way around—that one must first understand something before writing about it. To put the idea into a more ordinary academic context: it’s one thing to attend an economics lecture and leave with a notion of what “vertical integration” is, but quite another to define it in one’s own words, or to apply the concept to a particular firm, or to evaluate the practice by studying its practice in a variety of firms. Through the disciplines of choosing words, putting them into sentences, reviewing for accuracy, or to see if it even makes sense to an intended reader, students are using writing to inquire.

And then there’s “learning to write,” which must be a daunting proposition if you are coming from a field other than English. Future modules will present strategies and tactics helping students write college-level papers, but for now, it’s important to stress a few ideas that will help you ease your way in:

- You can’t teach them everything! Learning to write is a life-long endeavor, stopping only when the learner stops writing for good. Do not feel responsible to teach them everything, or fall into despair when they fall short on writing concepts you worked on in class. As a famous Roman rhetorician says, “Nature herself has never attempted to effect great changes rapidly” (Quintillian, Institutes of Oratory).

- Your students have learned a lot already. It’s the rare student who comes to Carroll completely ignorant of what a thesis is, or what paragraph is, or how to cite a source. They may not be as good as we want them to be, but they are pilgrims on the journey; they know how to walk.

- Students learn how to write by writing--not by you talking about writing (though some talk can help). Give them a space and a structure in which they can draft, reflect, get feedback, and try again. These actions will do more to help them learn than a perfect lecture about “the essay.”

- You can always ask for help. The director of Carroll’s Writing Center can provide you with resources and encouragement for any feature of writing you may feel uncertain about (and the director can also visit your class to present on a topic related to writing instruction). The Writing Center also has a staff of peer writing consultants who are trained to work with your students on any subject and on any part of the writing process.

In the principles that follow, we will be focusing on putting into action the concepts of writing to learn and learning to write.

1. Make Writing Projects the Main Building Blocks in Your Course

Most college courses organize themselves around areas of content, but to emphasize writing instruction, organize your course around writing projects. Think of each project as beginning with an area of collective inquiry around your chosen theme. Read about it; talk about it; do some informal writings around it; and most importantly, give students the space and direction to approach an issue through writing a more extensive piece about it. Think of that piece as the “capstone” for that project.

Keep in mind that the intent of FYWS is to support students in their quest to become better writers in academic settings. These conditions are typically met by thesis-driven essays and arguments that rely on close readings of texts, thoughtful exploration of one’s own experiences, values, and ideas in relationship to other perspectives that contest them.

It helps to give student writers direction by specifying a type of writing that can effectively respond to the issue or issues raised by the class’s exploration of a theme. Here are some examples from a few long-time writing instructors at Carroll with years of experience in first-year writing courses:

- In my (Jeff Morris’s) college composition course on money from liberal arts perspectives, the main building blocks support genres of essay: the personal narrative; the rhetorical analysis; the literary analysis; the literature review; the synthesis essay.

- In Debra Bernardi’s course on writing about horror, the main building blocks focus on the actions of writing: making specific arguments with specific evidence; writing about a horror text; writing about an issue that “horrifies” you to a person who may be able to do something about it (aka, a proposal); research and writing about a horror text in a historical/cultural context; writing about horrors in one’s own life through a revision of the third essay.

How many major assignments? The consensus in Carroll’s English program is four, though some do three, and some five. Given the objectives of FYWS, four or fewer makes the most sense. With project cycles of four to five weeks, your students can dig into your theme, generate writing ideas, write multiple drafts, and get feedback between them. And it is to that idea of project cycles that we turn next.

Taking Action, 2.1

For “writing to learn,” create a list of ideas, topics, issues that you want your readers to explore and write about, and put down as many as you can. Then, consider which three or four could be thematic anchors for the writing projects that will structure your first-year writing seminar. For “learning to write,” consider what genre or type of writing you want to see at the end of that inquiry: a personal narrative, a proposal, an extended definition, a position paper, an argumentative essay, a literary or rhetorical analysis, a book review . . . ?

2. Build Repeatable, Predictable Processes into your Writing Projects

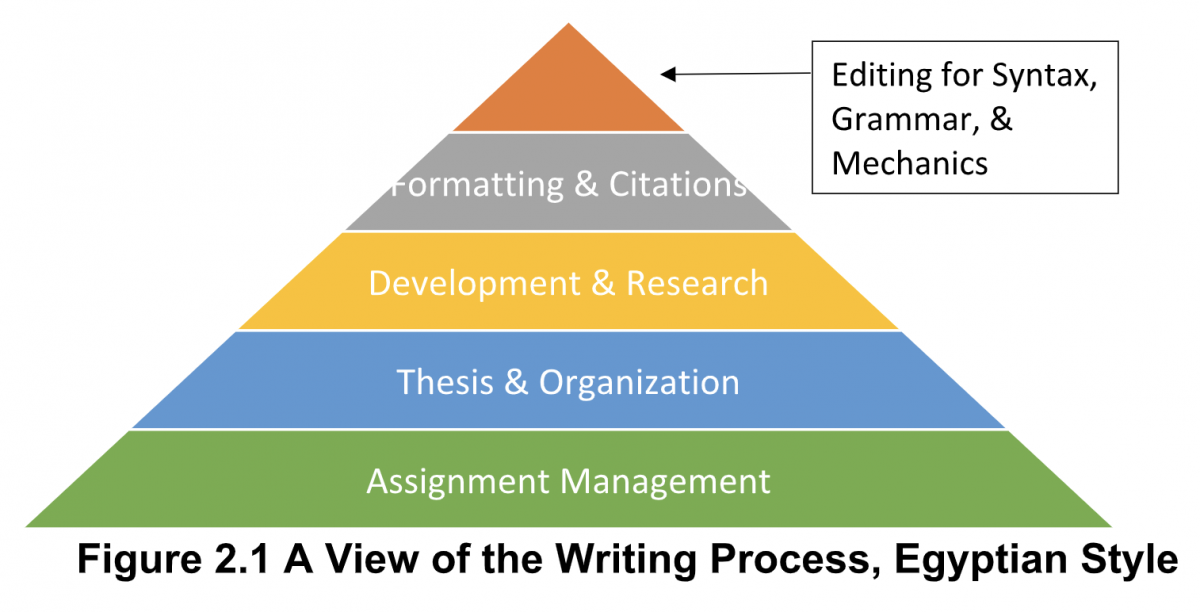

Figure 2.1 shows crucial writing activities for the bulk of academic, thesis-driven papers. Think of it as the student writer’s food pyramid:

From a stable base of assignment management, you can bring some order to the necessarily messy, open-ended, often frustratingly slow process of writing a paper. Table 2.1 provides more detail that suggests a clear, repeatable sequence that can shape the writing projects in your seminar.

Table 2.1 Helping Your Class Manage the Writing Process

| Phase 1: Orientation | Introducing the writing project |

| Phase 2: Exploration | Engaging students in the issues and themes they may write about in their capstone for the unit: Here’s where you enjoy sharing readings with them, discussing ideas, doing field work, asking for little scraps of writing that may help them articulate their ideas, settle into a topic, or set a persuasive goal for a paper. |

| Phase 3: Choosing | Encouraging students to make decisions about their topic and their scope; who their audience is, and how they want to affect them (ie., “before reading my paper, my readers think “x” about this issue; but after reading my paper, they will think “y” about the issue). They may be ready to articulate a tentative thesis, but they may need to change it as they progress through Phase 4 and beyond. |

| Phase 4: Planning | Re-engaging with seminar reading, learning activities material and perhaps new sources to: discover ideas; develop evidence; and arrange points to fulfill the purpose and/or the thesis of the essay. |

| Phase 5: Drafting | Writing the paper. This phase also implies that in the process of writing, a student discovers problems with the initial plan, whether it’s in the purpose, the thesis, the organization, the evidence, or the adopted tone (too formal, not formal enough). |

| Phase 6: Workshopping | Receiving feedback from peers, the instructor, or writing center consultants. Understanding the feedback, deciding what to act on and how. Note: this cycle can be done more than once in a project or use more than one source of feedback. |

| Phase 7: Revising | Rewriting the draft in light of feedback and the student’s own developing awareness of how to make the paper more effective. |

| Phase 8: Editing | Attending to page design (aka “formatting”); editing for sentence variety and effective syntax; editing for grammar and mechanics; editing for integration of sources and correct citation according to the demands of the assignment. |

Please understand that listing these activities in sequential order gives the misleading impression that there is a completely rational, linear, or even lockstep process to writing a paper. In reality, students might explore the project’s theme (phase 2) while choosing a topic or point of view they want to convey (phase 3). Similarly, a student may get some feedback in a writing conference with you (phase 6) that makes them realize they need to choose an entirely different direction for the paper (phase 3). While these overlapping and recursive features are natural parts of the writing process, they must play out against a background of progressive steps toward a final draft.

There is trial and error in discovering how much time to spend on each project as well as each phase within a project. A somewhat helpful resource can be the writing assignment calculator from the University of Portland’s writing center. Although it is intended for student planning and does not include the exploration phase so critical to our seminars, you can enter a start and end date that will give you an idea of how much time you could set aside for choosing a topic, gathering evidence, drafting, rewriting, and editing.

But as you probably realize from your years of teaching, there is never enough time, and you cannot predict how much time a student needs for any phase in any project. Flexibility is the watchword, especially the first time through a writing-intensive course.

Taking Action, 2.2

Building on one or more of your ideas for a writing project, try mapping out that project from introducing the assignment to the submission of the final draft. How many sessions do you need to devote to exploration, choosing, planning, and drafting? When and how will you build in feedback? How many sessions, if any, would you include for editing?

3. Include Low-Stakes Assignments to Support Major Papers

The Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing promotes the importance of curiosity, openness, flexibility, and creativity, but if students are only asked to turn in a final draft, it diminishes their interest in these critical habits of mind as they wonder simply how to get a good grade on the paper. By introducing a few low-stakes assignments into each project cycle, you help them to embrace these habits. Low-stakes writing encourages them to try things out, take more risks with their ideas, try to see issues in new ways, and express themselves in ways they might not if the stakes are high.

In other words, they are more likely to engage in writing to learn.

Consider, therefore, including a few low-stakes writing activities to promote some of the phases of your assignment cycle. Reflection pieces work well in the exploration phase. Assigning a tentative purpose statement or thesis on a three-by-five card can support their efforts to choose a direction. A required paragraph plan or outline can solidify their planning.

And then, there is freewriting. Popularized by Peter Elbow in Writing without Teachers, freewriting challenges a writer to put down whatever is going on in the mind without stopping the pen or computer, and when the writer cannot think of anything else to write, they can simply repeat “I don’t know what to write” repeatedly until something occurs to them as it inevitably will. Freewriting helps the writer escape the dismal voice of the inner censor—a voice you may be familiar with yourself. It imposes upon you all kinds of judgments and fears that, while important in later stages of writing, will impede creative and honest expression while discovering, planning, and drafting. Freewriting creates a lot of garbage too, but frequently there is treasure in the rubbish. You can learn more about free-writing, focused free-writing and other brainstorming strategies on Carroll’s Writing Center website.

Some writing teachers require students to keep a course log or journal in which students are regularly asked to do low-stakes writing. It’s a handy way to assign, collect and assess their efforts, and can either be a physical notebook or a file they share with you via Google Docs or Moodle.

There are so many ways to help students write to learn. The WAC Clearinghouse (WAC stands for Writing Across the Curriculum) has an excellent webpage that introduces you to nineteen low-stakes, writing-to-learn activities:

- The reading journal

- Generic and focused summaries

- Annotations

- Response papers

- Synthesis papers

- The discussion starter

- Focusing a discussion

- The learning log

- Analyzing the process

- Problem statement

- Solving real problems

- Pre-test warm-ups

- Using cases

- Letters

- What counts as a fact?

- Believing and doubting game

- Analysis of events

- Project notebooks

- The writing journal

You will have to find your own balance point regarding how many low-stakes writings you assign and how you will monitor them. After all, you have more to do than just this seminar! Also, some students are skeptical about the worth of low-stakes writing, but if you take the time to collect them and respond to their thoughts but not the quality of writing, they may become believers. If nothing else, regular (and swift!) evaluation of these efforts will encourage most to take them seriously (see Module 1.3).

Taking Action, 2.3

Go to the WAC Clearinghouse and learn about one writing-to-learn activity you might be interested in trying. Then, thinking about that activity in connection with a piece of content of your course, write a paragraph about how you plan to use it, why you think it will work, and any doubts you may have about its potential to work.

4. Sequence Projects from Easier to More Difficult . . .

. . . and then, not so difficult. To help students build confidence and ability, make your first writing challenge the easiest of your major writing projects. Many writing teachers will begin with an assignment that leverages students’ personal experience, but there is a healthy debate in composition circles about whether the personal narrative has a place in courses intended to teach writing for academic settings. In any case, begin with what you estimate to be the easiest of the challenges, then build up from there, encouraging improvement as you make successive assignments a larger part of the final grade.

But make your most challenging project the next-to-last assignment. This approach seizes on the prospect that your students—and you—still have reserves of energy before the final three weeks of the semester. By encouraging a peak effort before end-of-the-semester fatigue sets in, you give first-year writers a better chance to shine. And it gives you a better chance to provide meaningful feedback that they will take seriously. Very few students pay attention to the final comments of the last paper, nor do many professors do their best work in grading them during finals week.

Therefore, consider ending with a project that is more reflective of the course as a whole—what has been learned, what has changed as a result of a semester-long inquiry into a fascinating subject. Such an assignment that synthesizes readings and experiences across the whole course can be rigorous, and it can also help you learn about the course and give everyone concerned an opportunity to celebrate.